In today’s digital age, Online IDentity Theft (OIDT) is a growing concern affecting millions of people worldwide.

As users, we directly generate data – related to physical, emotional, social status – and consent to its storage by accepting more invasive but less perceptible forms of surveillance and, in this sense, normalise our ‘being online’ as a prosthesis of offline life. In other words, we live in the Endopticon system (Maturo, 2020) where control is subcutaneous, molecular.

Being surveilled – sharing data and information, then – is an individual responsibility that we assume even if not always consciously. On the contrary, we are often confident to manage contemporary unlimited and unpredictable risks.

When personal information is stolen and misused, victims often find themselves trapped in a socio-emotional turmoil that can be just as damaging as the financial consequences. Understanding the psycho-social experiences of these victims is crucial to foster empathy and provide appropriate support.

One of the crucial aspects that emerged from the empirical psycho-social research conducted by the University of Bologna was the socio-emotional impact that OIDT had on the victims who participated in the study.

The study refers to the results of the social research conducted with 43 European OIDT victims. The victims interviewed were divided according to their level of education in basic skills to cope with and manage the experience of digital theft and are:

- 93.6% expert victims

- 6.4% non-expert victims.

Social consequences: fear of anticipated stigma

The stigma attached to OIDT is linked to the way society perceives the victims. In the case of OIDT, the narrative often focuses on the active role and therefore co-responsibility for what happened to them since they must respond to the perpetrator. This view tends to downplay the level of sophistication involved in fraudsters’ techniques (Button and Cross, 2017; Cross, 2015; Drew and Cross, 2013). There is evidence that these social attitudes toward victims of fraud have consequences for victim assistance and help request.

As was the case with the victims participating in the study, overconfidence in one’s digital competence, underestimation of risks fuels discourses of Victim Blaming (Cross, 2018) and fear of so-called anticipated stigma (Reinka et al., 2020). This is the concern that society may not only judge but also discriminate (Reinka et al., 2020) if it learns of an event that affects them and that could potentially undermine their social authority. Familiarity with negative labels might even remind them of times when they themselves have discriminated or witnessed discrimination against a group of people (Reinka et al., 2020; Goffman, 2009).

Furthermore, the expert is considered a non-ideal victim (Cross, 2018) a person who, being neither weak, inexperienced nor elderly, is less likely to be morally supported by experiencing guilt for having played a role in his or her experience.

Denouncing and exposing oneself publicly, in fact, may be perceived as a fear of secondary victimisation that could manifest itself in not denouncing and remaining invisible.

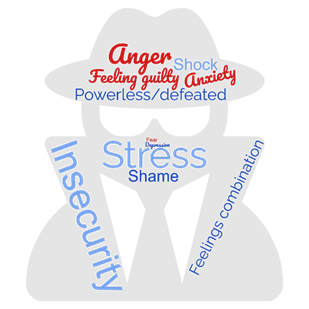

Emotional consequences

The psychological consequences cited by the OIDT victims were: 10.6% insecurity and stress; 6.4% anger; 4.3% helplessness/shock, anxiety, shame, guilt, fear; 2.1% depression and 25.5% feelings combined.

These feelings are all the more frustrating the higher people’s IT skills and social authority. Indeed, cross-referencing the psychological mood with the level of expertise of the victims, shame and guilt for not being able to foresee the risk emerge from the experienced victims (100%). Non-expert victims seem either to have no perception of their own emotional state (66.7%) or simply feel powerless/defeated (33.3%).

Thus, OIDT can affect anyone. Experienced users included. There are factors that accumulated together build conditions of “social fragility” by increasing or underestimating risk exposure. Thus, if the responsibility for the victimisation falls “socially” on the victim, the more frustrating the feelings will be the higher the victim’s digital skills and authority in the social role.

Universita di Bologna

References

Button, M., & Cross, C. (2017). Cyber frauds, scams and their victims. Routledge.

Cross, C. (2015). No laughing matter: Blaming the victim of online fraud. International Review of Victimology, 21(2), 187-204.

Cross, C. (2018). (Mis) understanding the impact of online fraud: Implications for victim assistance schemes. Victims & Offenders, 13(6), 757-776.

Drew, J. M., & Cross, C. (2013). Fraud and its PREY: Conceptualising social engineering tactics and its impact on financial literacy outcomes. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 18(3), 188-198.

Goffman, E. (2009). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Simon and schuster.

Maturo, A. (2015). Doing things with numbers: The quantified self and the gamification of health. Eä (Buenos Aires), 7(1), 87-105.

Reinka, M. A., Pan‐Weisz, B., Lawner, E. K., & Quinn, D. M. (2020). Cumulative consequences of stigma: Possessing multiple concealable stigmatized identities is associated with worse quality of life. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 50(4), 253-261.