Progress and digital transformation of the society have provided criminals with new opportunities to obtain and misuse personal identity information. Online Identity Theft (OIDT) is an example of this. Very little is known about the profile, needs and experiences of people whose identity information has been compromised or misused. OIDT European victims often do not report the crime, believing that the harm suffered is not significant enough.

One of the main aspects of the psycho-social empirical research conducted by University of Bologna was to profile the victims who participated in the study. To understand, with which type of “vulnerable population” we are interacting. We consider “vulnerable” a population characterized by a series of individual and contextual factors that could isolate them and not support them, exposing them to further victimisation.

Therefore, qualitative research with 43 structured interviews with OIDT victims has been conducted to outline a first profile. In this regard, the most important socio-demographic variables collected through the structured interview are gender, age, level of education.

Gender

Many studies and research (Guedes, Martins, Cardoso, 2023; Barnes, et al., 2020) point out that there are gender differences in the probability of risk of experiencing digital identity theft. The impact of individual variables on online victimisation such as gender have a significant effect on risk exposure (Al-Shalan, 2006). The gender dimension is considered one of the key social determinants for understanding online identity theft victimisation, i.e. exposure to potential perpetrators, target suitability and protection in the online context (Guedes, Martins, Cardoso, 2023).

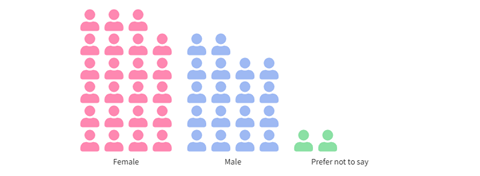

The victims who responded to the interview are: 53.5% Female, 41.9% Male while 4.7% prefer not to say about the gender.

Figure 1: Victims’ interview respondents gender

Furthermore, this factor together with other socio-demographic variables such as age and education level are considered the best predictors of risk of OIDT that are crucial for future containment and prevention strategies.

Age

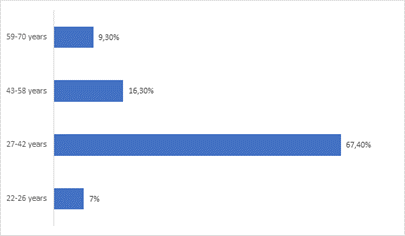

In the analysis of historical and social phenomena, age provides us with hints about the relevant generational cohort. Specifically, during the analysis, age was aggregated in the following order:

- 22-26 years: Generation Z

- 27-42 years: Millennials

- 43-58 years: Generation X

- 59-70 years: Baby Boomers

Figure 2: Victims’ interview respondents age

Millennials, the population aged between 27 and 42, are the most affected (67.4%). This is followed by Generation X (45-58 years) with 16.3%. While the cohorts at the extremes – baby boomers (9.3%) on the one hand and Generation Z (7%) on the other – are the least affected in the reference sample.

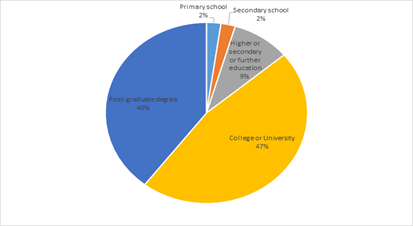

Level of education

Educational qualification is considered in the literature to be even more influential than employment status on the levels of digital literacy, learning and awareness acquisition. In the sample analysed, the victims had a high level of education: 47% attended College or University and 40% obtained a Post-Graduated degree. While 9% got higher or secondary or further education, 2% secondary school and 2% primary school.

Figure 3: Victims’ interview respondents level of education

Starting from the gender prevalence of the interview respondents, this factor has been subjected to a series of cross-tabulations between available socio-demographic variables (e.g. age and level of education).

- Gender * Age

Cross-referring gender to age, the victims responding to the interview are concentrated as follows 100% women in the 22-26 age group; in the 27-42 cohort 51.7% are women and 44.8% are men; and with the same percentage of men and women, 42.9% are concentrated in the 43-58 age group and 59% in the 59-70 age group.

- Gender * Level of education

Crossing gender with education level, 70% of the victimised women attended College or University while 52.9% of the victimised men obtained a Post-Graduated degree.

References

Al-Shalan, A. (2006). Cyber-crime fear and victimization: An analysis of a national survey.

Barnes, T. D., Holman, M. R. (2020). Gender quotas, women’s representation, and legislative diversity. The Journal of Politics, 82(4), 1271-1286.

Guedes I., Martins M., Cardoso C.S. (2023). Exploring the determinants of victimization and fear of online identity theft: an empirical study. Secur J, 36: 472–497. Doi: 10.1057/s41284-022-00350-5.